Deconstructing “Cliffhanger”

A “Cliff Notes” Story

March 2012

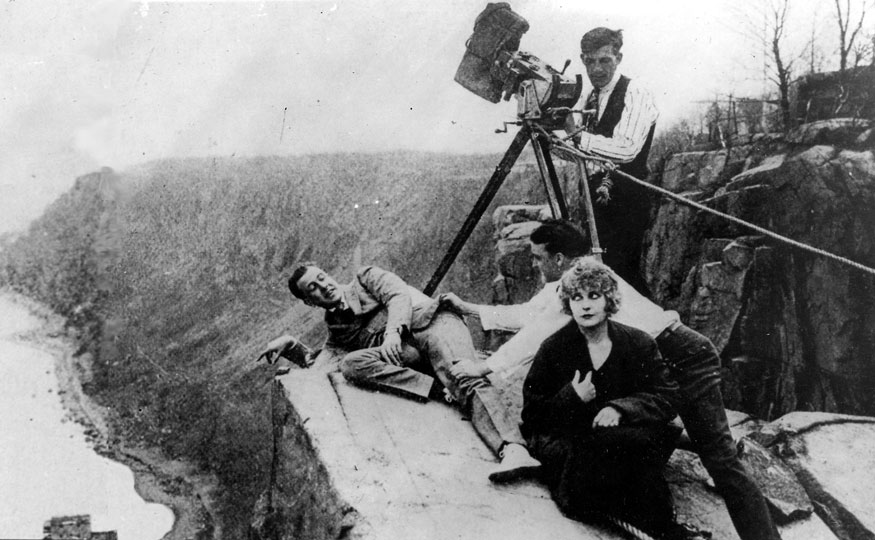

Three men and a woman are clustered on a bleak cliff edge, a big hand-cranked camera ready to roll. For local history buffs, the black-and-white image has become iconic: silent movie-making on the Palisades, before southern California and its sunshine lured the fledgling industry away. (The swashbuckling nature of early filmmaking comes across in how the camera is tethered to a heavy rope — but not the cameraman…) It’s easy to forget that the icon was also a moment captured in time, that these were four people — young people — at a specific moment in their lives.

Pathé Studio publicity shot of Pearl White and crew on “Cliffhanger Point” for 1918’s House of Hate courtesy of the Fort Lee Film Commission. Present-day image of the same site by Anthony Taranto. (Move the slider to toggle between the images.)

The cameraman is Arthur Miller (not that Arthur Miller!) from Roslyn, on the north shore of Long Island. He’s twenty-one and already a veteran, thirteen when he started out as an assistant cameraman. He’s filmed newsreels, features, serials — including Pauline. (Decades from now he’ll write a memoir about being a kid when the movies began, how they took the ferry across the Hudson from the city, the trolley through the woods and up the Palisades to a dirt-road town called Fort Lee. How it “never occurred to any of us that this small rural town would soon become the movie capital of the world, years before Hollywood, California, gained that title.”) As he gets set to roll, his heels are practically over the edge of the cliff.

The man lying there in the suit jacket, seemingly relaxed, smiling, his right shoulder and arm off in space, is George Seitz. He’s thirty years old, from Boston. He’s the director. He started out as a writer, three years ago helping to pen the epic yarn that propelled the serial format into a worldwide phenomenon: The Perils of Pauline, all twenty chapters, took theaters by storm in 1914. (It’s said that even the Czar of Russia is a fan.) Now Pathé, the Jersey City-based French company that produced Pauline, can’t seem to crank out the next serial soon enough. Or the next.

Holding onto George’s jacket is Antonio Moreno, also around thirty. He came to this country from Spain when he was fourteen. He’s making his name in the movies (as will Valentino) as the “Latin lover.” And this could be his biggest break yet: he’s starring with Pauline herself!

Under her trademark blond wig and the heavy eye makeup all actresses wear on screen, Pearl White (her real name) sits on the rocks wrapped in a heavy overcoat as they set up the shot. A farm girl from Missouri (the rest of her studio biography may be full of malarkey), she came East in 1910 to try her hand at the movies, in short films by production companies in New York, in Jersey, Connecticut, Pennsylvania — until lightning struck. By the end of 1914, Pathé had already released a fourteen-chapter follow-up to Pauline, The Exploits of Elaine. In 1915 came The New Exploits of Elaine (ten chapters) and The Romance of Elaine (twelve). 1916 saw The Iron Claw and Pearl of the Army — the Great War rages on in Europe — and 1917 brought Mayblossom and The Fatal Ring. For spring 1918 they are working on The House of Hate. She and Antonio are about to skitter down a rope over the ledge (you can see the rope slinking underneath her coat in the photo) as villains hurtle rocks and bullets after them. It’s old hat: as Pauline she dangled from a balloon, fought her way out of burning buildings, outran tumbling boulders, leaped into and out of automobiles and boats and trains and aeroplanes. All in a day’s work — and all Pearl, no stunt doubles. She is as much an athlete as an actress (and, in Miller’s memoir, a fun person to have worked with, no prima donna off camera). She’s become a wealthy woman, too. She drives a bright yellow Stutz Bearcat home to a seventeen-acre estate on Long Island. Still, grinding out a chapter every two weeks has taken its toll: some bad twists and sprains, a broken collarbone. Pearl White is twenty-eight years old when the shutter in the publicist’s camera clicks in front of that rocky ledge along the Palisades, in the Coytesville section of Fort Lee.

Her contract with Pathé will be up in a year.

Pearl White will leave the United States to move to Paris. She’ll make a few more films and star in some live revues, but mostly she’ll pursue other interests. She’ll buy a hotel and casino, keep a stable of race horses. She’ll marry and divorce, then take up with a young Greek millionaire. They’ll keep a house in Cairo and travel the world — without her wig, she will be able to enjoy some anonymity — coming to the United States at least three times to visit. (But not once in her life will Pearl White, the international movie star, set foot in California — or a little town called Hollywood.) Old injuries will lead her deeper into the dark of pain killers and alcohol. She dies of liver disease at the American Hospital in Paris in 1938, forty-nine years old.

George Seitz will make the trip with the movies to Hollywood. He’ll direct over a hundred films by the time of his death in 1944 at the age of fifty-six, including eleven of the sixteen Andy Hardy movies with Mickey Rooney (and, in some, a young Judy Garland).

Antonio Moreno will also move to Hollywood. He’ll marry an heiress named Daisy, buy a grand estate in the Los Angeles hills — but his accent will make the transition to sound difficult. He’ll hone his craft in Mexico, as both an actor and as a director (his 1932 film Santa is regarded as a classic). Back in Hollywood he’ll work as a character actor (see him in John Ford’s 1956 classic Western The Searchers — and in 1954’s Creature from the Black Lagoon). He’ll die in 1967 at the age of seventy-nine, having earned, like Pearl White, a star on the Walk of Fame.

Arthur Miller, the kid from Roslyn, will go to Hollywood, too. Working first at Paramount, then Fox, he’ll be nominated seven times for Academy Awards for cinematography. He’ll win three times: for How Green Was My Valley in 1942, for Song of Bernadette in ’44, for Anna and the King of Siam in ’47. He’ll retire in 1951, but still stay active as the president of the American Society of Cinematographers. In 1967 he’ll coauthor One Reel a Week, about the early days of movie-making. “When we landed at Edgewater, on the Jersey side,” he’ll recall, “it looked like another world to me … The experience of [being in Fort Lee] with actors, directors, and cameramen and hearing them swap stories, gossip, and ideas was delightful, and was something I enjoyed for the next few years.” Arthur Miller will be seventy-five when his final credits roll in 1970, out in California.

– Eric Nelsen –